by Mark Easton

Suggest northern Greece as a holiday destination and a fog of bafflement will descend across the furrowed brow of many a British traveller. Somewhat like iced tea and vegetarian sausages, northern Greece is clearly a contradiction in terms – a touristic oxymoron.

We know what a Greek holiday means: a pretty island harbour lined with whitewashed tavernas – and most definitely in the south. If we wanted “northern”, we’d go to Manchester. Or possibly Murmansk.

But such certainties may need to be shifted to the column marked “Greek myths”. These days, I submit, northern Greece makes perfect sense for British travellers in search of a bit more than a sunlounger and a carafe of the local retsina.

Classicists and geologists disagree about the origins of Halkidiki, the three-fingered claw reaching down into the Aegean. To the former, this is the scene of a battle between earthly giants and Olympian gods, a game of rock tennis that ended badly for the big guys. To the latter, it is the product of a volcanic embrace between the geotectonic units of the Vardar-Axios Zone and the Serbo-Macedonian Massif. Take your pick.

Either way, the result is a landscape as dramatic as an Aeschylus play, rugged red mountains plunging down to sandy coves, heavy with the scent of pine and flowering gorse.

The beaches are said to be the best on the Med. The Germans first laid their towels on them decades ago but have recently been jostling for the best spots with Russians and Ukrainians. The Brits, belatedly, are realising a direct flight to Thessaloniki can deliver you to this overlooked corner of Europe in the time it might take for a rush-hour train to judder from Dorking to Balham.

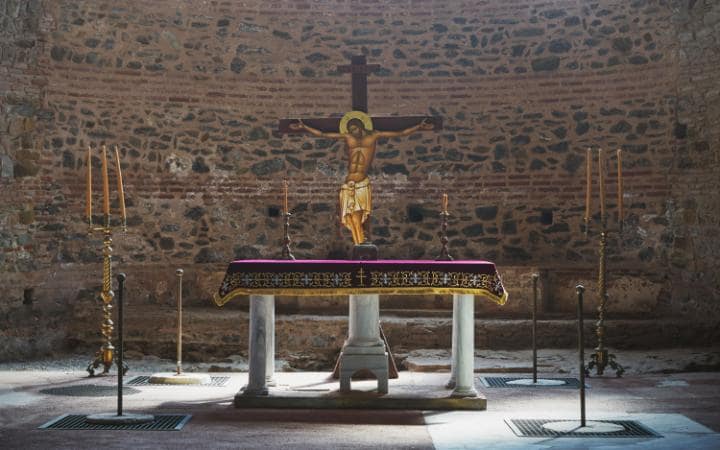

Thessaloniki is to the Balkans what Istanbul is to Asia Minor – an ancient and modern city sparkling with great museums and nightclubs that still echoes to the chants of rival civilisations. The Rotunda tells the tale. Erected at the beginning of the fourth century as a Roman temple, it was adapted as an early Christian church and decorated with glorious Byzantine mosaics before 16th-century Ottomans turned it into a mosque, complete with a minaret constructed from recycled lumps of church.

In 1912, Orthodox Christians took it back, dedicating its six-metre-thick walls and magnificent arches to dragon-slayer St George. It stands as a memorial to the battles of identity and ideas that have shaped this area, a cultural mash-up that should be on the bucket list of every adventurer who enters the mighty city walls.

The locals call the region Macedonia and barely conceal their fury that the name has been appropriated by a former Yugoslav republic and an Italian fruit salad. Tempers can run short in the Balkans and it doesn’t pay to debate the matter.

Instead, after taking one’s fill of beautiful Thessaloniki, one might head west across the fertile plains of the Aliakmonas delta, through peach and cherry orchards, past cotton and tobacco fields to Aegae, the ancient capital of the Macedons – now a small town called Vergina.

There are very few occasions when I have been heard to gasp in a museum. But in the Stygian gloom of a subterranean exhibition beneath a reconstructed tumulus in Vergina, my breath was quite taken away.

“What did you see?” you may ask. It is quite a tale. The story starts when King Philip II of Macedon was stabbed to death by one of his bodyguards at his daughter’s wedding in 336 BC. (Some suspect his son Alexander the Great may have been involved, but this is another question best left unexplored.) The king was cremated and his remains placed in a gold larnax inside a stone tomb buried beneath a Great Mound.

Despite the best efforts of centuries of grave robbers, there he stayed until 1977, when the spade of famed Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos tapped against the roof of the underground burial chamber. The ancient structure remains exactly where it was, reinterred after excavation, along with other royal tombs discovered on the site. But in glass cases just a few feet away are exhibited simply wonderful objects found inside – gold, silver and ivory artefacts in almost perfect condition. The most impressive to me was not the golden chest that contained Philip’s bones, nor the dazzling golden diadem that belonged to his pregnant wife, buried with him.

It was the gold wreath that had been placed on Philip’s head. Exquisitely and delicately wrought in the form of 313 oak leaves and 68 acorns, it is a piece of jewellery so stunning that I would travel to northern Greece just to see it.

Gold has long been this region’s great attraction. Foreign invaders fought for control of the mines from which the first gold coinage was minted and the very concept of money was born. Head over oak-crowned Mount Cholomondas, towards the birthplace of Aristotle at Stagira, and you discover that arguments over Greek gold are still as fierce as ever.

It might be judicious to go with a local guide. Protesters have painted out many of the road signs that lead you through magical fairy-tale forests. Buried treasure has excited strong passions in the mountains.

Better a drop of wisdom than an ocean of gold, as the Greek proverb goes. But wise counsel appears in short supply as Canadian-owned mining company Eldorado Gold looks to extract billions of euros’ worth of gold and other precious metals.

Village has turned against village – for some it is about desperately needed jobs and investment, for others it is about eco-crime and foreigners blackmailing the Greek state.

Following the official Aristotle anniversary in 2016, it is surely right to consider what the great philosopher would have thought about it all. A few miles from the mines is the place where he was born and, quite probably, where he was laid to rest. Stagira is well worth a visit – some villas and shops from the ancient town are being brilliantly restored.

The views of the sparkling Aegean from the town’s ancient stoa, a place where Aristotle almost certainly did some top-notch pondering, can barely have changed in 2,400 years.

If sitting there today, he might well have mulled over how the bickering over the gold mines is a symptom of a country trying to recover its self-respect amid the pain of austerity and the ignominy of foreign bail-outs. They are a people in search of a saviour and some think they have found him on Kassandra, the most westerly of Halkidiki’s three fingers.

Hotel owner Dr Andreas Andreadis has been described as “the man who saved Greece”. He took over the private Greek tourism confederation in 2010 and introduced a series of measures that coincided with a 42 per cent growth in tourist income even as the country’s GDP dropped 25 per cent.

“I do not want to be the Minister, nor the government,” he told me from his office overlooking Sani resort, the 1,000-acre luxury tourist development he started 30 years ago with a business partner.

“But if we do not jump-start the situation, nothing is going to happen.”

When faced with major embarrassment in the readies and reputation departments, it must have been tempting for Greece’s hoteliers to have returned to the mass-market strategy of the Seventies: cheap beer, oily chips and a lizard in the bidet. Instead, they have put quality before quantity, attracting international investors who recognise that the tourism fundamentals haven’t really changed since Aristotle.

“I see the last couple of years as very expensive psychotherapy for the Greek people,” Dr Andreadis said. “The good thing is we now have a more realistic government and an opposition that is very much more pro-business in nature.”

His own baby, Sani, has grown up and become a family of successful luxury beach resorts. Just around the bay is Sani’s little brother, Ikos (the male form of Ikea). It is an award-winning all-inclusive with 300 wines and Michelin-starred chefs. Each, in its own way, offers what Dr Andreadis calls aspirational European lifestyle – Mediterranean cuisines and fine wines for the discerning traveller and, beyond the gates of the resorts, a wealth of natural and cultural attractions that connect us with the ancient world.

Whether he saved Greece even the good doctor questions – but his greatest achievement is in starting to convince sceptical Brits that the mainland of northern Greece is not a contradiction in terms. Like morning cloud on Mount Olympus, the fog is lifting from furrowed British brows.

Mark Easton is the Home Editor for BBC News